March 2023 | By David Mann and Anushri Bansal, Mastercard Economics Institute

Consumer pent-up demand and excess savings drove significant tailwinds for economies in Asia Pacific in 2022. This year could be a different story. China’s removal of Covid-related restrictions could be positive for later in 2023, but the region could face certain headwinds with labor shortages, wage increases and continued inflation.

Since early 2022 when most Covid restrictions globally were lifted, consumers were more than ready to spend their accumulated excess savings on activities they were unable to do during the pandemic, including in-person retail, experiences and international travel.

However, businesses have struggled to meet consumer demand due to supply chain disruptions, the conflict in Ukraine and a shortage of service-related labor. This has led to higher prices across the board. In addition, the return of employees in some sectors remains slow and below trend. For example, the hospitality and health care sectors in Australia and New Zealand are seeing a tight labor market and higher wage pressures. Effectively, no product, no people and strong demand. Despite this, the pace of rising inflation mostly outweighs wage increases.

However, central banks may be concerned that sustained inflation increases could lead to more aggressive wage negotiations and higher labor costs. As a result, companies could raise prices for their products and services even more as their input costs increase. Economists refer to this potential risk as a wage-price spiral. The more central banks believe the threat to be real, the more businesses believe central banks will respond and keep prices contained.

Could we be heading to a wage-price spiral? Our answer is no. Historically, wage increases happen slowly. Moreover, fewer workers are unionized now than what we have seen historically, credible monetary policy is tightening in developed markets, including the markets we focus on in this blog, and global growth is slowing down in 2023 as noted in the Mastercard Economics Institute’s Economic Outlook 2023 report.

Consumers should see a return to normal demand and supply and labor and price dynamics. Why? Work-from-home remains popular in economies with higher internet penetration. Jobs with lower contact and less labor-intensive sectors have also adopted hybrid work.

Meanwhile, high-contact services and labor-intensive sectors, such as manufacturing and construction, are operating below pre-pandemic labor strength. As a result, prices should stabilize over the next 12-18 months, according to the Economic Outlook 2023 report. China’s re-opening could play a bigger role in easing supply-side disruptions, more than what we had expected towards the end of last year.

Staggered re-openings across Asia Pacific also implies that economies that opened in early 2022 could see some cooling off domestically as pent-up demand slows down. On the other hand, industries like travel and hospitality could see a return of workers as wages and opportunities in these sectors remain strong. In addition, tech layoffs could mean an end to the large-scale wage increases seen over the last few years.

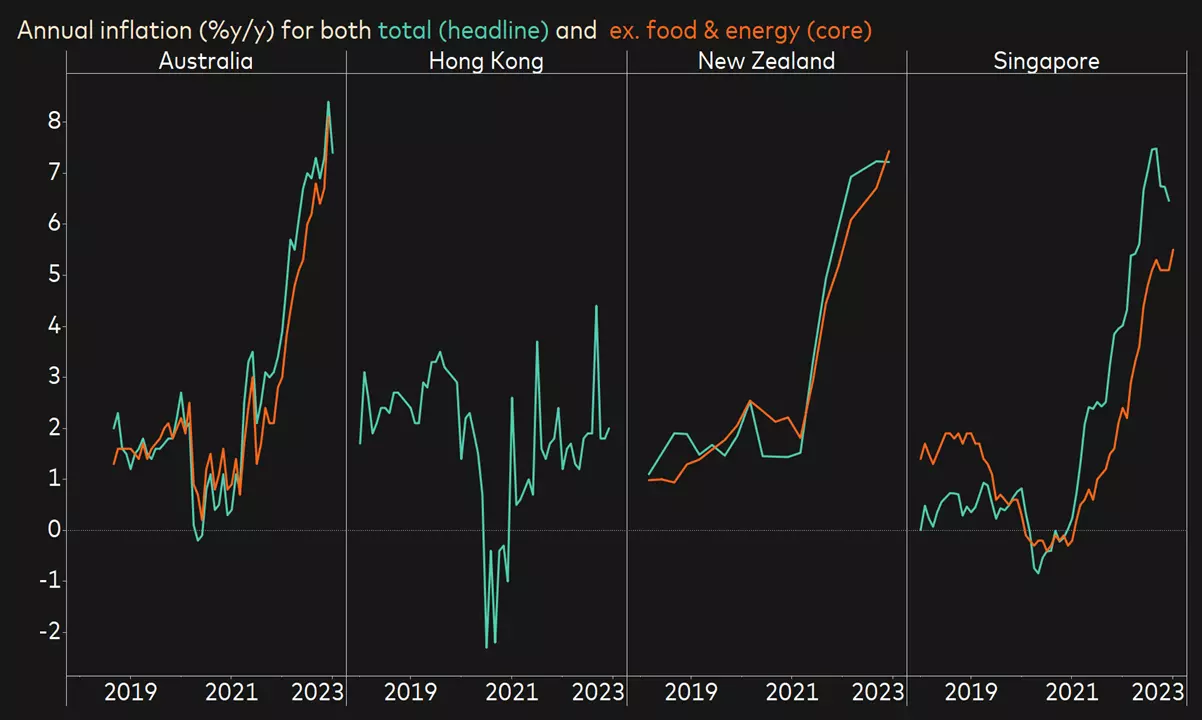

With that in mind, we look at the inflation-labor market dynamics across four Asian-Pacific economies – Australia, New Zealand, Singapore and Hong Kong.

Inflation: the perfect storm in 2022

Shortages in essential commodities and supply-side disruptions worsened as economies re-opened and consumers were ready to spend their excess savings. Consumers saved more than they would have had they been able to do normal activities, such as traveling and eating out. Just as this supply and demand imbalance was tipping, the conflict in Ukraine started, causing disruptions in food and energy markets. This led to pervasive price increases for everything from toiletries to salon services and airline tickets.

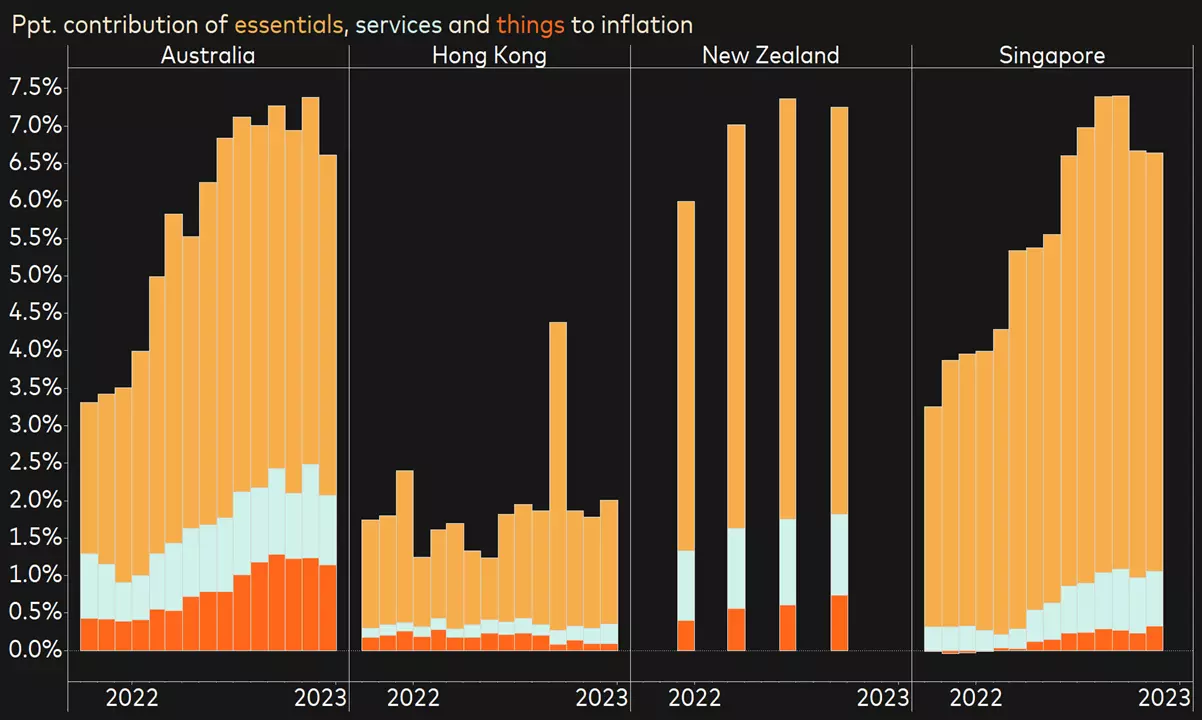

The biggest increase and contributor to inflation is essentials, including food, fuel, utilities, rent and mortgage payments. However, prices for services, such as going to a cinema hall, eating in restaurants, and monthly mobile phone payments, have also increased.

Chart 1: Core inflation (excl. food and energy) has increased along with headline numbers

Source: CEIC, Mastercard Economics Institute

Source: CEIC, Mastercard Economics InstituteHong Kong doesn't have a core inflation series

Chart 2: Essentials - food, fuel, utilities, housing – contribute the most to inflation pressures

Source: CEIC, Mastercard Economics Institute

Source: CEIC, Mastercard Economics InstituteEssentials are defined as food, housing, transportation, utilities

Services are defined as health, communication, recreation, education, financial services

Things are considered clothing & footwear, home furnishings, durable goods

Covid-driven labor shortages could continue, underscored by aging population

One of the fallouts from the pandemic is the continued labor shortages in many economies, with people hesitant to return to certain high-contact services sectors. The “great resignation” also led to more permanent fallouts as roles such as caregivers left the workforce. In addition, migrant works have not returned at the same level and growing challenges with aging populations in most advanced economies, which are now also increasing in low- and middle-income countries.

Recent UN population projections show that by 2030, 1 in 6 people will be over age 60, and by 2050, two-thirds of people older than age 60 will be living in low- and middle-income countries. Based on our calculations and the UN’s migration assumptions, which assume zero migration rather than a return to pre-Covid migration trends, we could see 0.4ppts less real GDP growth in Australia in the coming years and 0.3ppts less growth in Singapore.

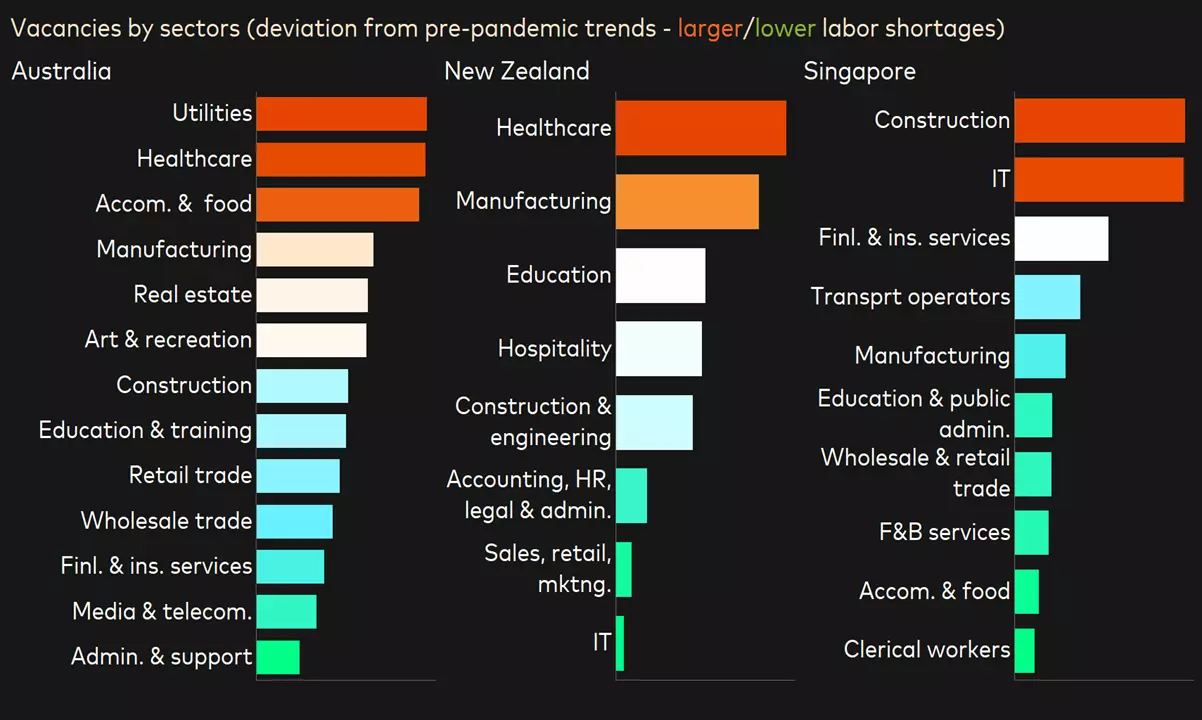

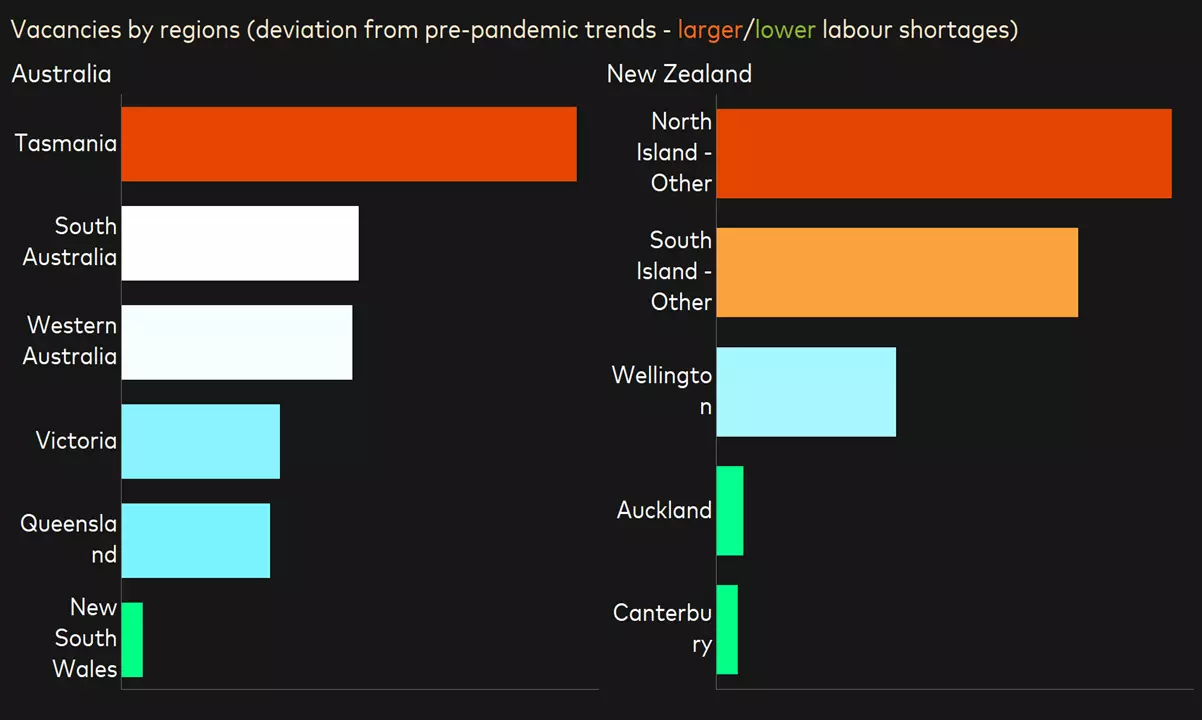

The hospitality and health care sectors face the most significant lack of workers compared to sectors such as IT and financial services. This is based on posted job vacancies in Australia and New Zealand since the beginning of 2021 compared to pre-pandemic trends. In addition, smaller towns and more remote locations in the two countries find it harder to attract workers than in the bigger cities.

By contrast, sectors in Singapore employing highly skilled workers are seeing more vacancies, in line with the tougher requirements for hiring foreign labor. This adds to wage pressure there, though only for some job types (see the vacancies data in chart 3).

Chart 3: Labor shortages across sectors and regions

Source: CEIC, Mastercard Economics Institute

Source: CEIC, Mastercard Economics InstituteNote: Bars show deviation of average vacancies from 2021 to November 2022 vs. pre-pandemic trends; data for Singapore is only until August 2022.

Wages rise despite a tight labor market and higher prices

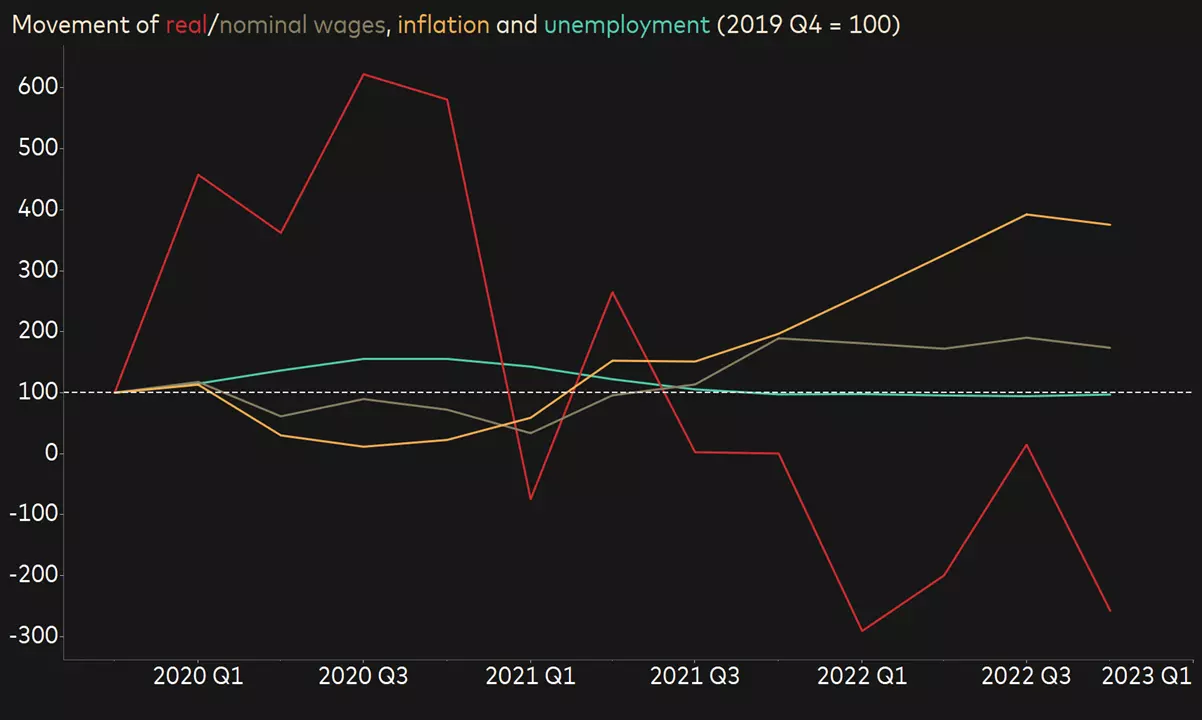

Labor shortages and inflation are leading some sectors to pay much higher wages to attract talent. Nominal wages (amount of money paid hourly or as salary) across countries have increased over the past few months, with unemployment rates remaining at all-time lows.

However, this rise in wages has not kept pace with the increase in prices, leading to a fall in purchasing power (lower real wages – wages that you get paid factoring in current inflation – and higher inflation would mean wages in real terms have fallen).

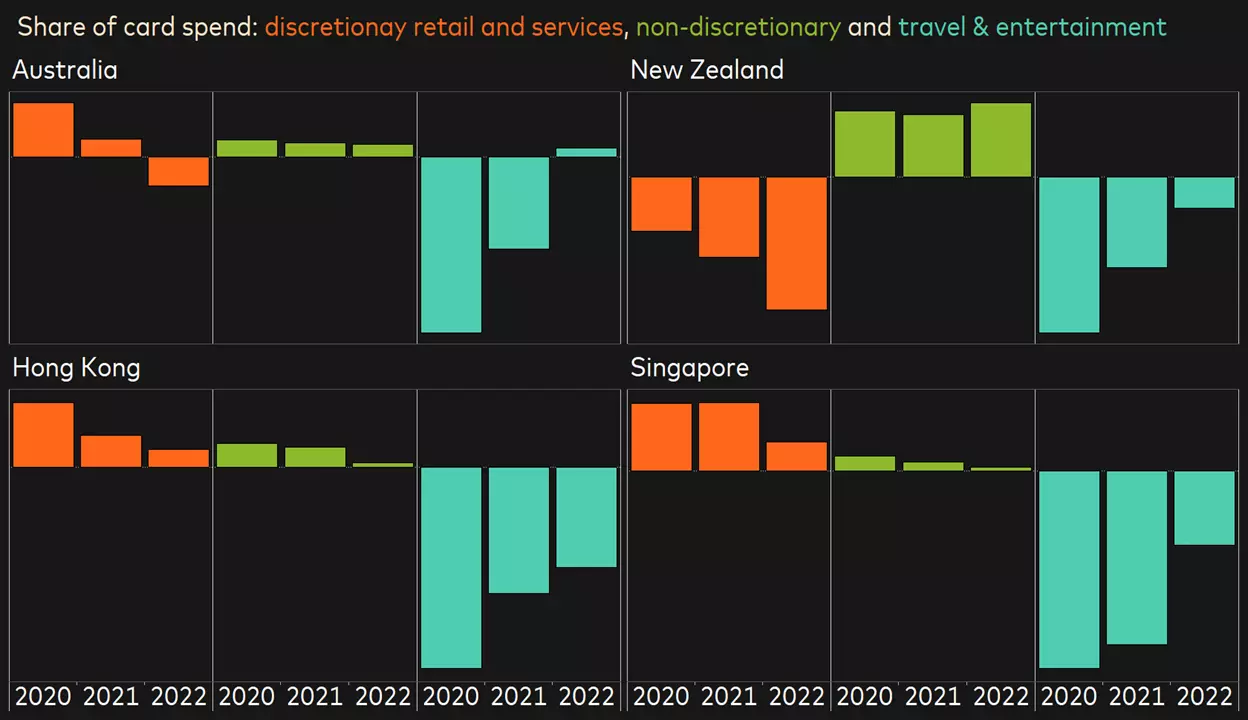

In addition, consumers globally are trading down on essentials to enable ongoing spending on experiences such as travel and hospitality. These previously ‘forbidden fruits’ have seen increased demand despite high prices, hurting discretionary retail and other services.

Chart 4: Today’s labor-price dynamics – tight labor market, rising wages, higher prices, lower purchasing power

Source: CEIC, Mastercard Economics Institute

Note: Bars show deviation of average vacancies from 2021 to November 2022 vs. pre-pandemic trends; data for Singapore is only until August 2022.

Chart 5: Travel & Entertainment (T&E) share in spend has been improving at the cost of discretionary retail and other services

Source: CEIC, Mastercard Economics Institute

Source: CEIC, Mastercard Economics InstituteHistory repeats itself: A closer look at similar past episodes for Australia

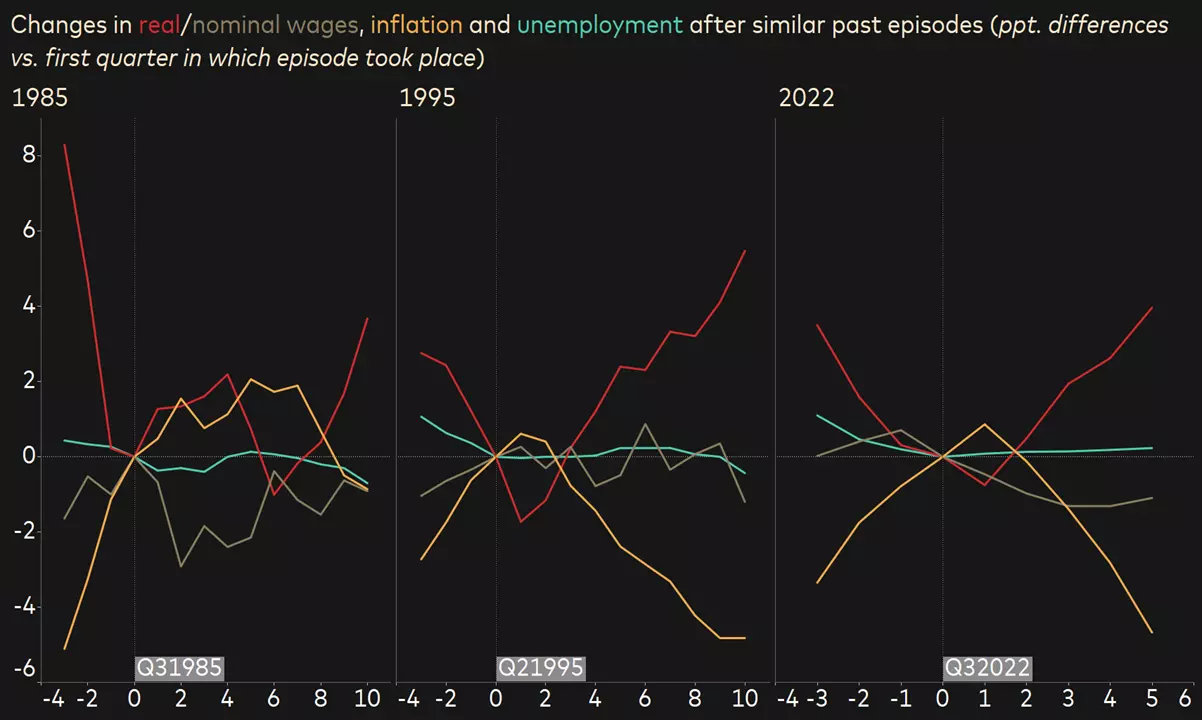

Persistently high inflation and a tight labor market are leading to speculation of a wage-price spiral - implying that prices and wages would keep increasing over a few quarters. However, based on historical cycles, we don’t believe the region is headed for a wage-price spiral. We looked at past episodes in Australia, where there’s been a similar combination of high inflation, increases in nominal wages, falling real wages and a tight labor market. Inflation has come down for a few quarters (with 0 on the x-axis being the beginning of the episode in chart 4), which would then lead to a rise in real wages, even while unemployment remained somewhat stable throughout.

In the current period, nominal wages haven’t kept pace with inflation, with the pace of growth either faltering or stabilizing. This could be for several reasons, including the sluggish nature of wage increases (most wage rises are contractual and would not be coincidental to rising prices) and the lower bargaining power of workers. Unionization has fallen over the past 60 years, from 53.8% in 1960 to 13.7% in 2018 (OECD) in Australia.

Moreover, monetary policy will also have a big role in thwarting demand and inflationary expectations, with central banks across the globe increasing rates at a rapid pace since the beginning of 2022. The U.S. Federal Reserve has raised rates by 475 bps in this cycle, and the Reserve Bank of Australia by 350 bps as of March 2023.

Overall, a credible tightening of monetary policy, the easing of supply chain pressures as the West sees weaker performance in 2023 (as reported in Economic Outlook 2023), and lower unionization mean we are unlikely to see a wage-price spiral.

What this implies for consumers is that as underlying demand and supply dynamics improve, prices could start to stabilize, improving real wages and purchasing power. In effect, during the next 12-18 months, these markets could come out of their state of dis-equilibrium and move towards normalcy of demand, supply, labor markets and prices. As a result, consumption growth may return to pre-Covid rates after prolonged pent-up demand eases.

Chart 6: Historical look at labor-price dynamics - low unemployment, rising wages, higher prices, lower purchasing power (quarters after the episode)

Source: Oxford Economics, Mastercard Economics Institute

Source: Oxford Economics, Mastercard Economics InstituteNote: x-axis is quarters before and after the event – with 0 being the quarter in which the episode began

DISCLAIMER: © 2023 Mastercard International Incorporated. All rights reserved.

This Mastercard Economics Institute presentation (This "Presentation") and content or portions thereof may not be accessed, downloaded, copied, modified, distributed, used or published in any form or media, except as authorized by Mastercard. This presentation and content are intended solely as a research tool for informational purposes and not as investment advice or recommendations for any particular action or investment and should not be relied upon, in whole or in part, as the basis for decision-making or investment purposes. This presentation and content are not guaranteed as to accuracy and are provided on an "as is" basis to authorized users, who review and use this information at their own risk. This presentation and content, including estimated economic forecasts, simulations or scenarios from the Mastercard Economics Institute, do not in any way reflect expectations for (or actual) Mastercard operational or financial performance. The Mastercard Economics Institute uses a multitude of data sets (public and proprietary) as well as models that are intended to estimate economic activity.

Holzer, H.J. 2022. Tight labor markets and wage growth in the current economy. Brookings Institute. https://www.brookings.edu/research/tight-labor-markets-and-wage-growth-in-the-current-economy/

IMF. 2022. Wage dynamics post covid-19 and wage-price spiral risks. World Economic Outlook. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO

Jorda, O. and F. Nechio. 2022. Inflation and Wage Growth Since the Pandemic. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Working paper series. https://www.frbsf.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/wp2022-17.pdf

Neyavan, S. and J. Bleakley. 2022. Wage-price Dynamics in a High-inflation Environment: The International Evidence. Reserve Bank of Australia. https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2022/sep/wage-price-dynamics-in-a-high-inflation-environment-the-international-evidence.html

WHO. 2022. Ageing and Health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health